The Bristol Somali Festival is a sister to the week-long Somali Festival in London that is curated by Ayan Mahamoud. This is year’s festival focused on the concept on Identity, Belonging and role of culture within the diaspora community. Thanks to the success of the last year’s Bristol Somali Festival, BSWN in partnership with M Shed and other partners were able to bring Somali Festival to Bristol once again for two days of discussion and activities aimed to celebrate the Somali community in Bristol.

The festival was launched on the evening of 27th October with an event hosted in partnership with M Shed. Key note speaker for the evening was Osman Mohamed Ali, founder of the Somali Museum in Minnesota, and other speakers included Dr Idil Osman, Artan Mohamed, Abira Hussein, Zahra Kosar and Aidarus Aidid. This discussion was followed by poetry reading of poetry by the Somali poet Xasan Daahir Ismaaciil Weedhsame translated by Martin Orwin.

The second day of the festival took place on Saturday the 28th October in the form of a large family day, an opportunity for families with young children to participate and enjoy being surrounded by Somali culture. The attractions included a fabric and craft store, craft tables, Somali kitchen for an experiences of blending spices, and an exhibition of Somali cultural artefacts.

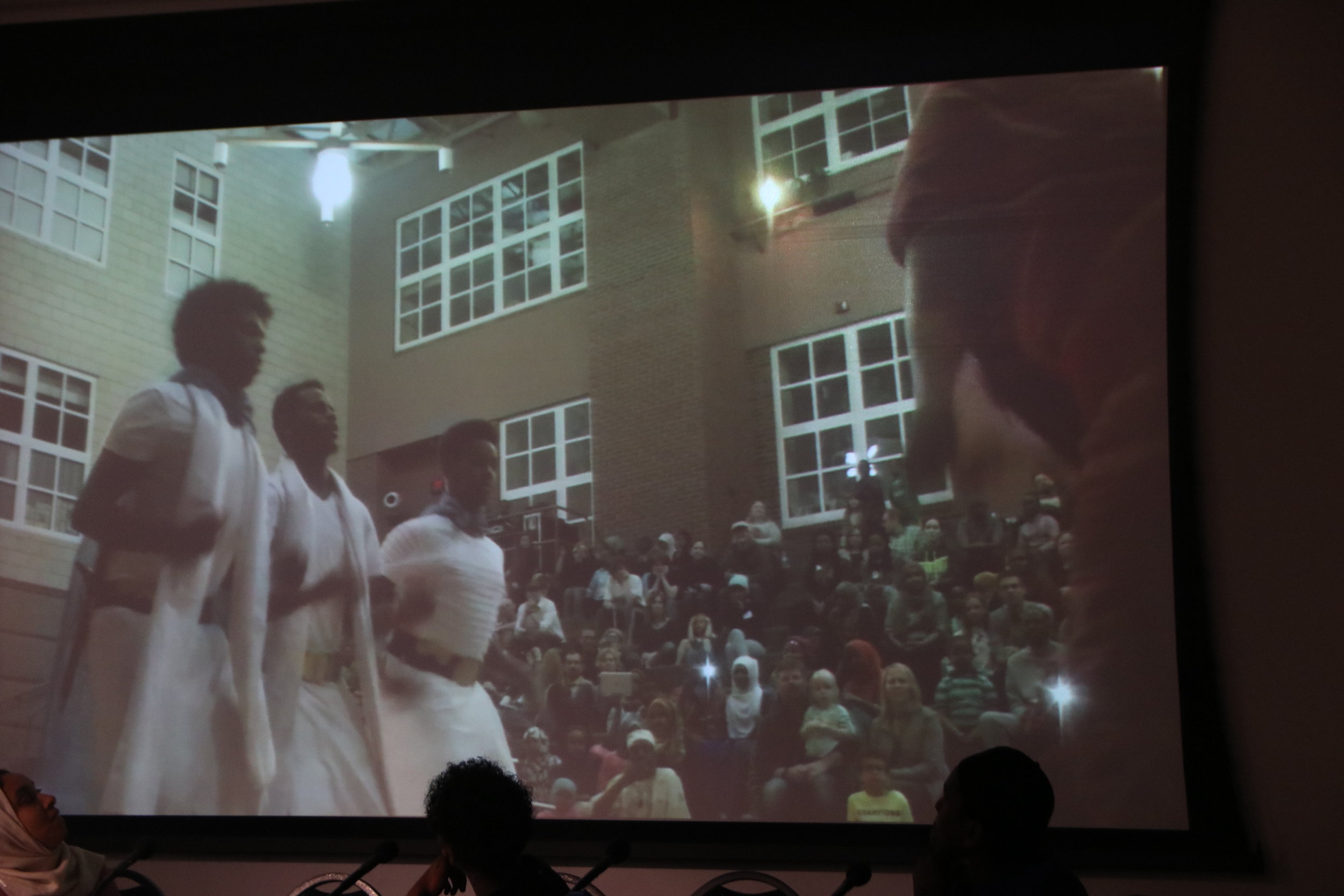

The second part of the day titled ‘Bristol Somalis talk frankly across the generations’ took place at Barton Hill Settlement where local Somali actors brought together the stories previously gathered in 4 separate workshops throughout August and September 2017. There, Bristol Somali mothers, fathers, sons and daughters each had their own space to talk about the pressures they’ve faced adjusting to life in Britain and what they would really like to discuss with other family members.

Please see below a transcript of the Launch Event discussion:

Key note speaker

Since 2009 up to today, I’ve been back and forth to Somalia, because I like to go there despite the instability and civil war. The reason why I learned about the culture was because I have been living in the diaspora my whole life and I wanted to find out more about my culture, my country and where I come from. When I was in Arabia, I was learning my culture, my language, I was kind of a leader for those who are living in diaspora and the young generation who are living in the different countries. So when I went to America, I tried to do something for myself first and then to help others understand their own culture. Minnesota is the country of the largest Somali diaspora. We have over 10,000 Somalis in Minnesota and I saw so much negativity in the US about the Somali community, whether in the South, or Somaliland. All Somalis are Somalis. Then I started to collect all our nomad artefacts, and make them too. I collected the traditional hats, the weaving things nomads used to make. And then I made a moving shop. Then I made classes for the community for the young generation who are going to raise their children to look at them with their culture and heritage, to know where they come form and where they belong to.

They all believed they are American and forgot where they come from. I want to remind them, wherever they are in the world, they are an immigrant in the eyes of others and they forget they have a land, a culture, a lot of opportunities so just to make a call of awareness to our community, I made this museum.

It cost me thousands of dollars to create it but all the community comes to learn from it. Once I taught the young children from elementary school about their heritage, that their grandparents used to make all these foods and things, they are proud and tell their parents about their heritage and learn more from their parents. So we try our best to connect the younger generation with their parents and their community, to bring them closer.

I traveled more than 8 times to Somalia to bring more artefacts and traditional hats to the US and we have over 750 artefacts on display from all over Somalia. Then we began to educate the non-Somalis to learn about our culture, and then we went to the schools, colleges, universities to deliver classes about our culture. Every day we receive messages curious about our culture and to learn more about the immigrants in their country.

We have a lot of resources in our country but it is not known at all. We are not ambassadors for our country and we are not talking about it enough and we need to be. In the eyes of other, we are different, we are immigrant, to some we are terrorists, and we will remain that way if we don’t talk about our culture to others. We need to build bridges between the communities to connect us all and to learn from each other.

The children that live here and grow up here, and will be a part of this community for many years need to be taught by their parents the language, it starts at home. Teach a child their own language and teach the child another language and it will not be lost, it will be able to learn more language and learn better from others. We need to start to spread the word to all families. Don’t speak in English at home, let your children learn the language at home, tell them the stories from your land, tell them about home and how you were as a child and what you learned when you were young. Both my children speak and write Somali because I fight for that. Let us all take care of our kids.

When I retire, I want to make sure I leave something for my community and that is why I built that museum. If we leave them a legacy, they will not be lost, they will know who they are and how to be. We have to be strong in our culture, our religion, and our language.

In our museum, all of the community claims it, they all contribute and all care about it. And our events are always very well attended by a large audience, always at least 1000 young people attending to connect with their culture. We put on a nomadic play, and 85% of our content is nomadic. A group of elders make the weaving and teach the younger generations how to keep their tradition. We teach Somali dance.

To learn more about The Somali Museum of Minnesota, please see here.

Panel Discussion

What does cultural heritage and identity meets to you?

Artan:

What I do through Looh press, I publish books on history, language and culture, and we focus on east of Africa but we expand in other areas as well. The topics we focus on are for the purpose of exploring the Somali heritage and culture. We bring out the materials in terms of culture, literature and heritage to the forefront and making it widely available and affordable. Not just to the local diaspora but also the Somalis back home. I recently came from Mogadishu two days before the bombing from Mogadishu international book fare and you can’t believe the hunger for culture and the passion of the young people. You know most of them can’t afford the books but they will come to the fare and buy these books to learn and expand their knowledge. We revive classics, translate some of the classical works to Somali so we spread the heritage in our native language. The English word comes from latin’ cultura’, which means to cultivate. They saw the farmer as the most advanced you could get. The Wnglish word developed to signify an artist that brings out the beauty of the mind. As a person who loves reading, history and exploring the facets of ones identity, I decided to make that my profession.

Zahra:

Identity is how you see yourself, when you ask yourself who you are. There is not a single definition, it is such a fluid and multi-faceted thing - how you see yourself personally and professionally. I would describe myself as Somali female, a woman from Somaliland, British-Somali or whichever comes first, so I have a lot of identity from my family and my heritage. The language I speak shapes me and connects my identity. My religion as well, I’m proud to be muslim and sometimes the media has negatively portrayed us and a few people have hijacked our religion and I often defend myself in the face of that portrayal. Also, my identity is my professional identity as a social worker I have to add that social justice principle in my life, in a positive way to make a change to the people who suffer. My culture has different shapes, in a home, how we problem-solve, we use our culture in negotiation with our problems. Your identity is not only about your clan, it’s complex.

Aidrus:

I work a lot with the Somali community who are unfortunately often victims of hate crime. I think it’s very subjective. I am a young British Somali male. Each of these are different. We have a Somali side, an appreciation for our heritage and for what our previous generations went through for us to be here. I also am British and speak English. Heritage is something you are born with and appreciate, and we should teach people about all these positive sides of our culture. I would let my British friends try our food, learn about our stories, it is something we are proud of and I can bring to the table. Sometimes it can bring you into a crisis, am I going to follow the British side where I live in, or the Somali side of our forefathers? We need to learn to see that as a thing to propel us into the future and celebrate equally. And Osman’s museum I need to visit, it would be a great opportunity for all of us.

How does that help us build the bridges in the society?

Osman:

Actually the culture and heritage is my identity and I believe in it. When I see all that together, I see myself there. To build a bridge in my culture, I have to know my culture. Who am I, what’s my identity, where do I come from? When I know all of that, I can tell the others about it, and build that bridge and spread the word. What we do most of the time back home in US is very American. We use the artefacts as tools to educate the Somalis about their heritage and the non-Somalis who want to learn. When you are building this bridge, the other communities need to know more about you. If they don’t know anything about you, there is no understanding. So you want to know more about the Somalis? If something happens to you and you have a Somali friend, if they ask you some personal questions, don’t worry about it. They are asking because they want to learn from you and to make an idea about you, because they came to the land of opportunity and they want to learn about the country and you as an American/European.

Abira:

I think it means my life to me. It can be fatal to not know your identity and culture. As someone who doesn’t have the best command of Somali language, I struggled to speak to my grandparents and I didn’t have that connection. I wasn’t able to access this whole other world that was a part of me. Language particularly is key because having this understanding can expect your self-esteem, your life expectancy. It affects all aspects all your life. Being able to know your culture will help you to be a better British citizen. You may be better integrated if you focus on where you live but knowing yourself and your heritage helps you better navigate that ever fluid identity within you.

People talk about somalis not attending museums but actually building that bridge is a two way process. The museums and other spaces needs to meet us in the middle, need to provide an opportunity, and to continue to make our culture available and digitise our culture in archives. Our history is not mainstreamed and schools often teach American black history but not British. Our history here in Bristol as sea men is long and should be wider known. The Somali community need to connect to their culture and the non-Somali communities need to make an effort to connect with the Somali community and engage us on equal ground. For a mother who doesn’t speak up about their culture as important and doesn’t speak up for their child that is objectified within their culture can have a negative impact and we need to shed more light on it.

Q: I’m part of Tanzanian diaspora. From one diaspora to another, what would you say are the key thing we focus on as diaspora, to bridge the two identities within us?

Artan:

It’s a journey of discovery. Everybody has a personal touch of how to discover their culture, whether you call it a host community or migrant communities. I do this through literature, especially books in various languages not even related to Somali and translate them for the Somalis. There are nomads everywhere in the world, and we are nomads in our roots. The world will always interchange culture and heritage. It’s a shame we are unpacking this as a modern idea, instead of looking at the commonalities we already know we have.

Zahra:

What Madge (AN: Dr. Madge Dresser) is doing is a great progress. It would be great to have a meeting of historians and cultural experts. Tanzanians speak Swahili, and we can learn common greetings, or take those items like in the museum to use as tools to connect. Little things make difference. You want to leave a legacy so take some initiative and connect withe people.

Q: Do you have any plan to go back home when old? Are you planning to go back for good.

Artan - Yes.

Zahra - Yes, but we are not just refugees. Even so every Somali person wants to go back.

Aidarus - Not sure, trying to keep my options open.

Osman - Already have house built there.

Abira - I’ve never been before. I think part of the problem for me is that longing to go back to go home can be a barrier, looking backwards on what we miss instead of looking forward. I think parents need to feel rooted here in order to connect those identities. For refugees, there is a lot of trauma that makes those roots difficult to make. I do, I think. A part of me is still missing, I might discover it.

Q: There are problems in intergenerational understanding, can we have recommendations how to provide understanding between the two generations?

Aidrus from a youth perspective:

The main thing is to speak together. It’s not something that happens in the community, of struggles from both sides. Parents struggling to talk about their past, and the children growing up in a country as a minority, not within their own people. There are only so many things we discuss with our parents because we feel like there are things we need to hide. What about talking to the children about the barriers and the things they may face forming up in Britain?

Zahra from a parent’s perspective:

One solution could be for parents to stop learning English from their children. There are schools and classes. Children need to learn at home about our language because everything else outside they learn in English. That will deny the child to learn their own mother tongue that is a lack of the baseline for their other languages.

Osman:

First the parent has to be very serious about what they are doing, they have to have the commitment to build a relationship with their child. Once they build a friendly relationship with their child, they can teach them a lot back to the child and give them attention and advice. The relationship can then grow. In that case they can be friends and openly share learning between each other. Once we commit to encouraging the children, they will have a hunger to learn and they will listen to you.

Q: How can we close the gap between the children and parents when we have parents that want to go back but we don’t know when they are going to go back?

Abira:

Most of my experiences of Somalia are second hand. the problem with integration is that it is hard to integrate here. you have a lot of parents who have poor social housing, minimal access to education, schools are difficult. If you’ve lived back in Somalia with some level of living in equality and belonging, then that can be very much a draw to go back.

Artan:

I was born in Somalia and am a refugee of civil war. I remember what home was like, I grew up in Holland, that’s my happy place. I live now in UK, and raise four boys. I have that sense of belonging in Somalia and want to go back, my children don’t have that. They don’t think we are here temporarily, this is home to them. At the moment, we are still unpacking things mentally, some of us think we have settled but half the suitcases are still packed. Some of us really want to stay here, and I don’t think they have yet been asked that question because they are too young to answer about long-term goals.

Q: What about contemporary culture? Many artists trying to take historical heritage forward, make contemporary Somali music?

Zahra:

Somali music connects with me, I love it. There are great modern musicians that are up and coming now. I don’t connect with the contemporary music, I like the old music. I’m quite proud to enjoy what I was brought up on, because I came here as an adult. We use a lot of metaphors in our music, for example in one song describe a woman as a camel because it makes sense to us, it’s a precious twist of language to us. It’s a perforative role.

Aidarus:

We’ve got a few artists, but we are integrated very well with the western-style music. There is not enough investment or attention given to Somali music, incorporate the old school and the new style contemporary music to keep the tradition going.